On December 1, 1948, the body of an unidentified man was found on Somerton Beach in Adelaide, Australia. He was well-dressed, appeared healthy, yet showed no signs of violence or struggle. In his pocket was a scrap of paper with two words torn from a rare Persian poetry book: “Tamám Shud” — “It is ended.” Hidden in the same book was an encrypted code that has defied codebreakers for over 75 years. To this day, no one knows who he was, how he died, or what the mysterious cipher means. This is the story of the Somerton Man — one of the greatest unsolved mysteries of the 20th century.

The Discovery

The morning of December 1, 1948, began like any other summer day in Adelaide. At approximately 6:30 AM, jeweler John Bain Lyons and his wife were taking their usual early morning stroll along Somerton Beach, a popular stretch of coastline just south of Adelaide’s city center.

As they walked, they noticed a man lying on the sand near the seawall, his head resting against the concrete steps. He was well-dressed in a white shirt, tie, brown knit pullover, and gray-brown trousers. His shoes were polished. One arm was extended outward, the other bent at the elbow. A half-smoked cigarette rested on his collar, as if it had fallen from his lips.

The Lyons assumed the man was sleeping or drunk and continued their walk. They would later recall seeing the same man in the same position the previous evening around 7 PM. Others had noticed him too — several beachgoers reported seeing the man lying motionless, occasionally moving his arm.

But by mid-morning, when police were called to investigate, it became clear this was no sleeping drunk. The man was dead. And the mystery of his identity would consume investigators for decades.

The Autopsy: More Questions Than Answers

The autopsy, conducted by pathologist Dr. John Burton Cleland, revealed a series of puzzling findings. The man appeared to be in excellent physical condition — between 40 and 45 years old, approximately 5’11” tall, with well-developed calf muscles suggesting he had been an athlete or dancer. His hands were soft and manicured, indicating he did not perform manual labor.

But the cause of death was impossible to determine.

Dr. Cleland noted several unusual observations:

- The man’s pupils were unusually dilated and uneven

- His stomach was congested with blood, and his spleen was enlarged to three times its normal size

- Internal organs showed signs consistent with poisoning, particularly by a cardiac glycoside or similar toxin

- Yet comprehensive toxicology tests detected no known poisons

- There were no injuries, no signs of violence, no needle marks

- Stomach contents included a pasty he had eaten shortly before death

Dr. Cleland’s conclusion was carefully worded: the man had died from “acute gastric hemorrhage” and heart failure, consistent with poisoning by an unknown substance. But what substance? And how had it been administered?

The Missing Labels

When police examined the man’s clothing, they discovered something odd: every single label and tag had been meticulously removed. His shirt, trousers, coat — all bore no manufacturer’s marks. The tags had been carefully cut away, not torn. This was deliberate.

However, investigators found laundry marks on some items: “Keane” on a tie, “T. Keane” on a singlet, and “Kean” (without the ‘e’) on a laundry bag found at the Adelaide railway station. Following this lead, police tracked down every person named Keane or Kean in the area. None were missing. None recognized the dead man. The laundry marks led nowhere.

The dead man’s possessions were equally cryptic:

- A half-empty packet of Juicy Fruit chewing gum

- Some matches

- Two combs (one in his pocket, one at the scene)

- A pack of Army Club cigarettes containing seven Kensitas cigarettes (a different, more expensive brand)

- An aluminum American comb typically carried by military personnel

- A half-smoked cigarette behind his ear

- An unused second-class railway ticket from Adelaide to Henley Beach

No wallet. No identification. No money. No keys. Nothing that would indicate who he was.

The Suitcase

Two weeks after the body was found, on January 14, 1949, a brown suitcase was discovered in the cloakroom at Adelaide Railway Station. It had been checked in on November 30 — the day before the man’s body was found.

The suitcase’s contents deepened the mystery:

- A reel of orange thread identical to thread used to repair a tear in the dead man’s trousers

- Multiple items of clothing with labels removed

- A stenciling brush of a type used by military or maritime workers

- A screwdriver and scissors

- Clothing including a dressing gown with “Chemist” printed on it

- Several pairs of trousers with unusual construction — tailored with felled seams, an American style uncommon in Australia

Notably absent: identification, personal papers, or any clue to the man’s name.

One pair of trousers had a hidden pocket sewn into the waistband — the kind of pocket used to conceal something valuable or secret. It was empty.

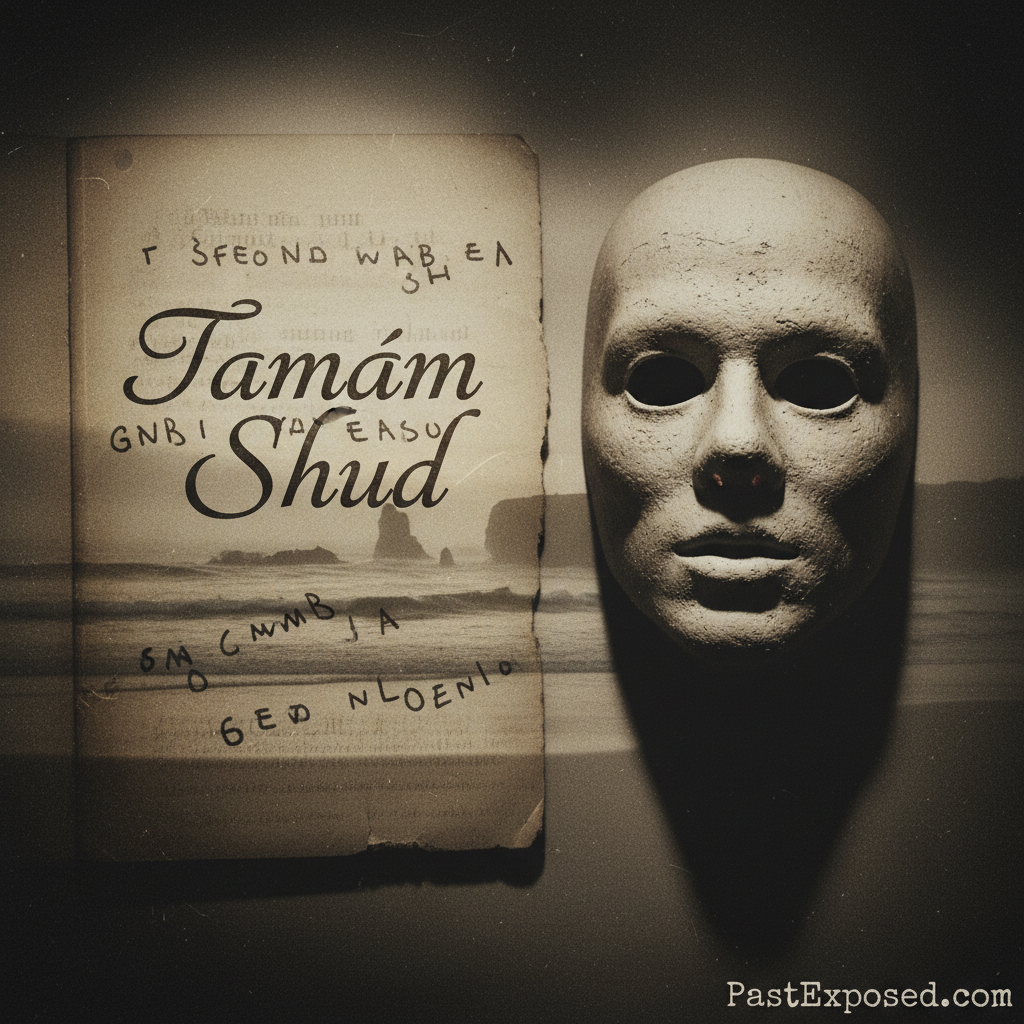

“Tamám Shud”

In April 1949 — four months after the body was found — police made a breakthrough of sorts, though it would only deepen the mystery.

Re-examining the dead man’s clothing, detectives found a small rolled-up scrap of paper tucked deep in a tiny watch pocket in his trousers, so small it had been missed in previous searches.

The paper bore two words, printed in an ornate typeface: “Tamám Shud” (also transliterated as “Tamam Shud”).

After consulting with academics, police learned these words were Persian, taken from the final page of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, a collection of 12th-century Persian poetry translated into English by Edward FitzGerald. The phrase means “It is ended” or “It is finished” — the last words of the poem.

Crucially, the paper had been torn from a book. It was not a printed note but physically ripped from a page. Somewhere, there existed a copy of The Rubaiyat missing its final words.

The Book and the Code

Police launched a public appeal: Did anyone have a copy of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam with the final page torn out?

In July 1949, a man came forward. He claimed that in late November or early December 1948 (around the time of the death), he had found a copy of The Rubaiyat thrown into the back seat of his unlocked car, which had been parked on Jetty Road, Glenelg — not far from Somerton Beach. The timing and location seemed too coincidental to be chance.

The man had tossed the book into his car’s glove box and forgotten about it until he saw the news reports months later. When he retrieved the book and examined it, he discovered the final page had indeed been torn out — matching the scrap found on the dead man.

But the book contained something else: On the back cover, written in pencil, was a series of seemingly random letters:

WRGOBABBABD

MLIAOI

WTBIMPANETP

MLIABOAIAQC

ITTMTSAMSTGAB

Below the letters was a phone number that had been crossed out (later traced to a nurse who lived near the beach), and what appeared to be a faint outline of letters visible when held up to light — possibly the impression left from writing on a page that had been torn away.

The code has never been broken. Despite being examined by military intelligence, codebreakers, mathematicians, and amateur sleuths for over seven decades, no one has definitively cracked what the letters mean.

Some theories suggest:

- It’s a substitution cipher

- It’s the first letter of each word in a message or poem

- It’s an abbreviation system known only to the writer and intended recipient

- It’s a one-time pad cipher (unbreakable without the key)

- It’s not a code at all, but random letters, initials, or a shorthand note

The deliberate crossing out of the phone number and the care taken to tear the page suggest these letters meant something. But what?

The Nurse

The phone number crossed out in the book led police to Jessica Ellen “Jo” Thomson (née Harkness), a 27-year-old nurse living on Moseley Street, Glenelg — a short distance from where the body was found.

When detectives showed Thomson a plaster cast of the dead man’s face (a standard procedure at the time), witnesses reported she seemed shocked, even distressed. She said she did not recognize him, but her reaction suggested otherwise. Some observers claimed she nearly fainted.

Thomson told police that during World War II, while working at a hospital in Sydney, she had owned a copy of The Rubaiyat which she had given to a man named Alfred Boxall, a lieutenant in the Australian Army who had been stationed in Sydney. She and Boxall had had a brief romantic relationship before he was deployed.

Could the Somerton Man be Alfred Boxall?

Police tracked Boxall down. He was alive, well, and living in Sydney. He still had the copy of The Rubaiyat that Thomson had given him, intact with all pages present. He was not the dead man.

So if Boxall wasn’t the Somerton Man, why did the mysterious book with the code end up in a car near Thomson’s house? Why was her phone number written (then crossed out) in the book? And why did she react so strongly to seeing the dead man’s face?

Thomson refused to say more. She maintained she did not know the man, and investigators could not prove otherwise. She died in 2007, taking whatever she knew to her grave.

Who Was He?

Over the decades, the identity of the Somerton Man has been the subject of endless speculation:

Theory 1: Espionage

The timing — 1948, at the beginning of the Cold War — has led many to speculate the Somerton Man was a spy. Australia was a strategic location, and intelligence operations by both Western and Soviet agents were active in the region.

Evidence supporting this theory:

- The removed labels (standard espionage tradecraft to prevent identification)

- The code in the book

- The unusual tailoring of his clothes (possibly foreign-made)

- The possibility of poisoning by an exotic substance

- The hidden pocket in his trousers

- His apparent physical fitness and the care in his appearance

Theory 2: Romantic Tragedy

The “Tamám Shud” note — “It is ended” — and the romantic poetry suggest a possible suicide related to a love affair. Perhaps the man and Jo Thomson had a secret relationship. Perhaps he was the father of her son, Robin Thomson, born in 1947 (whose physical features some observers noted bore a resemblance to the dead man).

Could the code be a final message to Thomson? Could the man have come to Glenelg to see her one last time, been rejected, and taken his own life?

Theory 3: Criminal Activity

Some investigators theorized the man was involved in smuggling or black market operations and was murdered to prevent him from talking. Post-war Australia had active black markets, and criminal organizations used poisoning as a method of silencing informants.

The Physical Evidence

Several unusual physical features of the Somerton Man have added to the mystery:

- Missing lateral incisors: Both upper lateral incisors (the teeth next to the front teeth) were absent. This is a relatively rare congenital condition.

- Unusual ear structure: His ears had a distinctive shape, with the upper ear hollows larger than the lower, a trait found in only 1-2% of the population.

- Hypodontia: He was missing several teeth congenitally (not lost to decay or injury), another uncommon condition.

- Highly developed calves: His calf muscles were unusually developed, suggesting he was a dancer, runner, or someone who regularly wore high heels (as was common for men in certain dance styles or professions).

These unique features should have made identification easier, yet no one ever came forward to claim him.

Modern Investigations

In the 21st century, advances in forensic science have brought new hope to solving the mystery.

DNA Testing

In 2021, South Australia Police exhumed the body of the Somerton Man for DNA testing. Using modern forensic genealogy techniques — the same methods that identified the Golden State Killer — investigators hoped to finally put a name to the unidentified man.

In July 2022, researchers announced a potential breakthrough: they believed the Somerton Man was Carl “Charles” Webb, an electrical engineer from Melbourne born in 1905. The identification was made through DNA genealogy and family tree research.

However, as of now, this identification remains disputed. Some family members of Charles Webb dispute the connection. Final verification through dental records and other documentation is ongoing.

The Code Remains Unbroken

Even if the man’s identity is confirmed as Charles Webb, the central mystery remains: What does the code mean? How did he die? Why were his labels removed? What was his connection to Jo Thomson? Why was he carrying “Tamám Shud” in his pocket?

These questions may never be answered.

Cultural Impact

The Somerton Man case has inspired:

- Countless books, documentaries, and podcasts

- Academic papers on cryptography analyzing the code

- Multiple stage plays and musical works

- A novel by Kerry Greenwood (Tamam Shud)

- References in television shows including Doctor Who

- A permanent place in popular culture as one of Australia’s greatest mysteries

The case has become a cultural touchstone in Australia, symbolizing the unsolvable mystery, the perfect enigma that refuses to yield its secrets despite every effort of science and investigation.

The Gravestone

For decades, the Somerton Man lay in Adelaide’s West Terrace Cemetery under a headstone that read simply:

“Here lies the unknown man who was found at Somerton Beach, 1st December 1948.”

In 1995, a new plaque was added with the words “Tamám Shud,” ensuring that even in death, the mystery followed him.

His exhumation in 2021 disturbed this resting place, bringing him back into the light of investigation one more time. If the identification as Charles Webb is confirmed, he may finally get his name back. But even then, so much will remain unknown.

On a summer morning in 1948, a man lay down on Somerton Beach and died. Or perhaps he was already dead when he was placed there. We don’t know. We don’t know who he was, where he came from, or why he carried a scrap of Persian poetry in his pocket. We don’t know what the code means or if it means anything at all. We don’t know if he was a spy, a lover, a criminal, or simply an unfortunate soul who died alone and unmourned. Seventy-five years later, the mystery persists. The code remains unbroken. The questions remain unanswered. And somewhere, perhaps, there is a truth waiting to be discovered — written in cipher on the back of a book of poems, or buried in memories that died with those who knew him. The waves still break on Somerton Beach, washing away footprints in the sand, just as time has washed away the identity of the man who lay there. But the mystery endures, a cipher that may never be solved, a riddle whispered across decades: Who was the Somerton Man? And what did he want us to know?