On the morning of January 15, 1947, a mother walking with her young daughter in a vacant lot in Los Angeles made a discovery so horrific it would haunt the city for decades. What she initially thought was a discarded store mannequin was actually the severed body of a young woman—drained of blood, surgically bisected at the waist, and posed with disturbing precision. The victim would become known as the Black Dahlia, and her murder would become the most famous unsolved case in Los Angeles history, spawning countless theories, confessions, books, and films. Over 75 years later, despite one of the largest investigations in LAPD history, no one has ever been charged with her murder.

The Discovery

Betty Bersinger was walking with her three-year-old daughter on Norton Avenue in the Leimert Park neighborhood of Los Angeles, heading to a shoe repair shop. It was a clear, cool morning, and the vacant lot at 39th Street and Norton Avenue was a shortcut she used regularly.

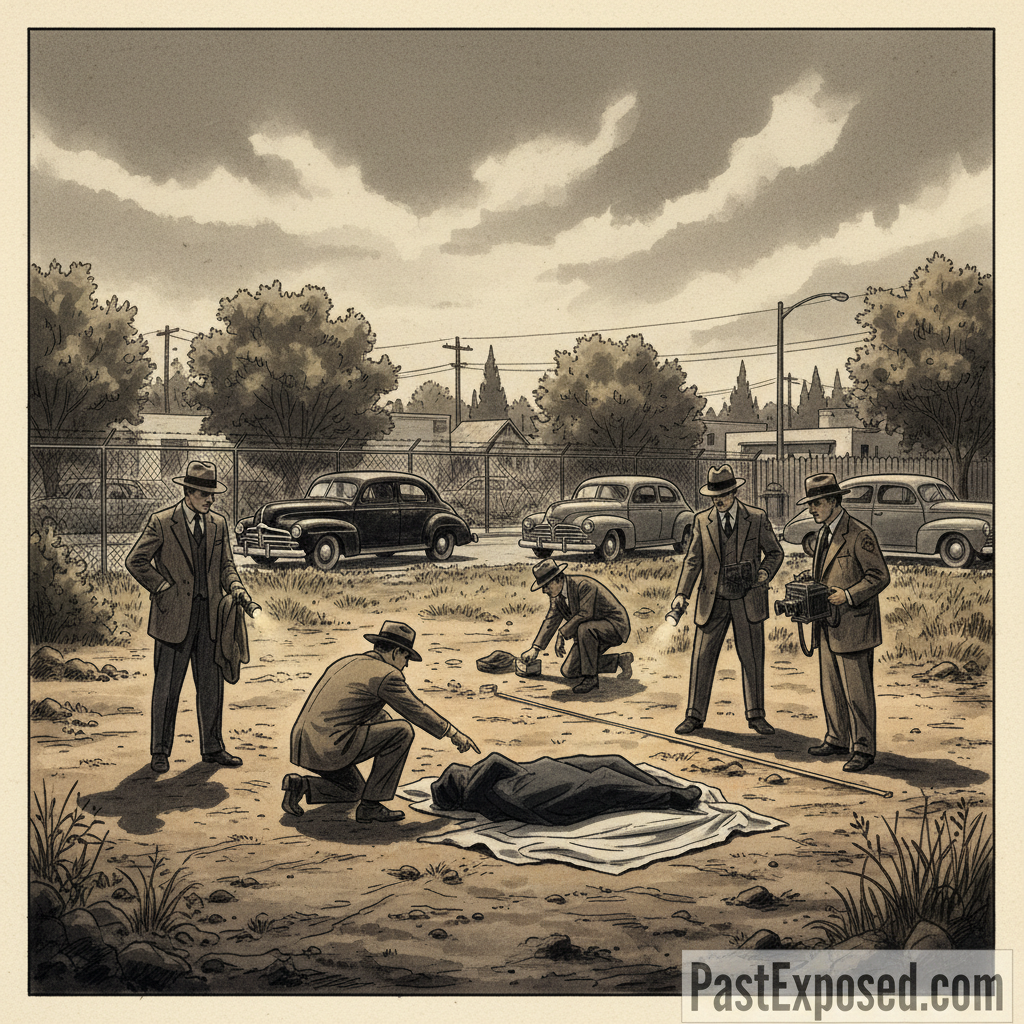

At approximately 10:00 AM, something in the weeds caught her eye. From a distance, it looked like a broken department store mannequin, discarded in two pieces. But as she drew closer, the horrifying truth became apparent: it was a human body, cut cleanly in half.

Bersinger grabbed her daughter and ran to a nearby house, pounding on the door and screaming for someone to call the police. Within minutes, LAPD officers arrived at the scene. What they found would become one of the most disturbing crime scenes in American criminal history.

The Crime Scene

The body of a young woman lay in the grass, approximately 10 feet from the sidewalk. She had been completely drained of blood, giving her skin a pale, almost translucent appearance. Her body had been surgically severed at the waist, and the two halves were positioned about a foot apart. Her face bore deep cuts from the corners of her mouth to her ears—a mutilation known as a “Glasgow smile” or “Chelsea grin.”

The crime scene revealed several chilling details:

- The body was clean: She had been thoroughly washed, with no blood present at the scene

- Surgical precision: The bisection showed considerable anatomical knowledge, with the body cut cleanly between the second and third lumbar vertebrae

- Posed deliberately: Her arms were raised above her head, and her legs were spread apart—clearly arranged by the killer

- No identification: No clothing, personal effects, or identification were found near the body

- Severe mutilation: In addition to the bisection and facial cuts, there was evidence of torture and sexual assault

- Cause of death: The coroner determined she had died from hemorrhage and shock due to the lacerations to her face and concussion of the brain

The body had been placed in the vacant lot sometime during the night or early morning. Given the amount of blood that should have been present, investigators immediately concluded she had been killed elsewhere and dumped at the location—this was a secondary crime scene.

Identification: Elizabeth Short

The victim had no identification, and her fingerprints initially yielded no results from standard law enforcement databases. However, LAPD detectives had the idea to send her fingerprints to the FBI. Through this broader search, she was identified within hours.

Her name was Elizabeth Ann Short, a 22-year-old woman originally from Medford, Massachusetts. She had been fingerprinted years earlier when she worked briefly at the commissary of Camp Cooke (now Vandenberg Air Force Base) in California during World War II.

Elizabeth, known to friends as “Beth” or “Betty,” had moved to California in 1943, drawn like thousands of other young women by dreams of Hollywood stardom. She was beautiful—5’5″ tall, with striking features, fair skin, and dark hair that she sometimes dyed jet black. She favored dark clothing and heavy makeup, which later contributed to her posthumous nickname.

The moniker “Black Dahlia” was coined by newspapers shortly after her death, likely inspired by the 1946 film noir “The Blue Dahlia” and her preference for black attire. The name stuck, and Elizabeth Short’s identity became forever intertwined with the gruesome circumstances of her death.

The Investigation Begins

The Black Dahlia case became an immediate sensation. The LAPD launched what would become one of the largest investigations in its history, eventually assigning over 750 personnel to the case and interviewing more than 150 individuals of interest.

Detectives began piecing together Elizabeth’s final days:

January 9, 1947: Elizabeth was staying at the Biltmore Hotel in downtown Los Angeles. Multiple witnesses saw her in the hotel lobby that evening. She told the desk clerk she was meeting someone and would be checking out. She was seen speaking to a person at a pay phone, then walking out of the hotel. She was never seen alive again by anyone who has been publicly identified.

The six days between January 9 and January 15 (when her body was discovered) represent a complete mystery. Where was she? Who was she with? Where was she killed? These questions have never been definitively answered.

The Autopsy

The autopsy, conducted by Dr. Frederick Newbarr, revealed horrifying details:

- Time of death: Approximately 10-12 hours before her body was discovered

- Cause of death: Hemorrhage and shock due to concussion of the brain and lacerations of the face

- The facial lacerations (Glasgow smile) were inflicted while she was still alive

- Evidence of blunt force trauma to the head

- The body had been bisected after death

- Complete exsanguination—every drop of blood had been drained or washed away

- Evidence suggesting the killer had considerable anatomical knowledge

- Stomach contents included what appeared to be feces, though this finding remains disputed

The level of mutilation suggested the killer had spent considerable time with the body after death. The surgical precision of the bisection indicated possible medical knowledge or experience as a butcher. The thorough washing of the body and the careful positioning suggested obsessive attention to detail.

The Suspects: An Ever-Growing List

Over the decades, literally hundreds of people have been considered as potential suspects in the Black Dahlia murder. Some were investigated by police; others were proposed by amateur sleuths, journalists, and family members years after the fact. Here are the most prominent:

George Hodel

Perhaps the most compelling suspect emerged decades after the murder. Dr. George Hill Hodel was a Los Angeles physician, a brilliant intellect with a dark reputation. He was investigated by LAPD in 1949—two years after Short’s murder—for alleged sexual abuse of his teenage daughter, Tamar.

In 2003, retired LAPD homicide detective Steve Hodel (George Hodel’s son) published “Black Dahlia Avenger,” in which he presented evidence that his father was the killer:

- George Hodel had medical training sufficient to perform the bisection

- He lived near where Elizabeth’s body was found

- Police had placed bugs in Hodel’s home in 1950, and recordings captured disturbing statements

- Hodel was connected to Los Angeles’ surrealist art scene; some researchers see parallels between the posed body and surrealist art

- Handwriting analysis suggested possible matches between Hodel and taunting letters sent to police

- After his daughter accused him of sexual abuse in 1949, he abruptly left the country

However, critics note that much of this evidence is circumstantial, and the LAPD has never officially confirmed George Hodel as a suspect.

Mark Hansen

Mark Hansen was a nightclub and theater owner who Elizabeth knew and had stayed with briefly before her death. Some of Elizabeth’s belongings were found at Hansen’s home. He had a collection of photographs of young women, and Elizabeth’s name appeared in his address book.

Police investigated Hansen thoroughly but found no evidence directly linking him to the murder. He remained a person of interest but was never charged.

Leslie Dillon

In 1948, a man named Leslie Dillon contacted LAPD, claiming to have information about the murder through a friend named “Jeff Connors.” When detectives questioned Dillon, his stories became increasingly suspicious, and he demonstrated detailed knowledge of the murder.

However, Dillon had an alibi for the time of the murder—he was working in San Francisco—and despite polygraph tests and extensive interrogation, there was insufficient evidence to charge him. Some investigators believed Dillon was involved, possibly with an accomplice, but could never prove it.

Robert “Red” Manley

Robert Manley was a 25-year-old married salesman who had dated Elizabeth briefly and was one of the last known people to see her alive. He dropped her off at the Biltmore Hotel on January 9, the night she disappeared.

Manley was extensively questioned and took multiple polygraph tests, all of which he passed. He voluntarily provided detailed accounts of his time with Elizabeth and cooperated fully with police. Investigators eventually cleared him, though he remained haunted by the case for the rest of his life.

Other Suspects

Over the years, numerous other individuals have been proposed as suspects:

- Woody Guthrie: The folk singer was briefly investigated after being mentioned in connection with Elizabeth, but no evidence linked him to the crime

- Orson Welles: The director was living in Los Angeles at the time and was a notorious womanizer, but this theory is entirely speculative with no supporting evidence

- Various doctors and surgeons: Given the surgical nature of the bisection, medical professionals were investigated

- Norman Chandler: Some conspiracy theories implicate powerful Los Angeles figures, though these theories lack credible evidence

The Media Circus

The Black Dahlia case was a media sensation from day one. Newspapers competed ferociously for scoops, sometimes compromising the investigation in the process. Reporters swarmed Elizabeth’s family in Massachusetts, intruded on crime scenes, and even may have contaminated evidence.

The killer appeared to enjoy the attention. Within days of the murder, the killer allegedly sent packages to newspapers and the police containing:

- Elizabeth’s personal belongings, including her birth certificate and social security card

- An address book with the name “Mark Hansen” written on the cover

- Taunting messages constructed from cut-out letters pasted on paper, reading phrases like “Here is Dahlia’s belongings” and “Letter to follow”

The promised letter never arrived, or if it did, it was never released to the public. However, numerous other letters claiming to be from the killer flooded into newspapers and police stations—most were determined to be hoaxes.

False Confessions

One of the most frustrating aspects of the investigation was the sheer number of false confessions. Over 500 people confessed to killing Elizabeth Short, including:

- Attention seekers wanting notoriety

- Mentally ill individuals convinced they had committed the crime

- People turning themselves in to escape other problems

- Pranksters and publicity hounds

Each confession had to be investigated, wasting thousands of hours of police time and resources. This phenomenon continues to this day, with new “confessions” occasionally emerging.

Theories About the Motive

What could drive someone to commit such an elaborate, theatrical murder? Several theories have been proposed:

Sexual Psychopath

Many criminologists believe the killer was a sexual sadist who derived pleasure from torturing and mutilating his victim. The staged positioning of the body, the extreme mutilation, and the care taken to clean and present the corpse all suggest a deeply disturbed individual with a compulsion to display his work.

Medical Professional Gone Mad

The surgical precision suggests someone with anatomical knowledge. Some theorists believe a doctor or medical student committed the murder, possibly as a twisted experiment or fulfillment of violent fantasies.

Revenge or Silencing

Some theories suggest Elizabeth knew something dangerous or was involved in something that made her a target. The extreme nature of the mutilation could have been intended as a warning to others.

Misogyny and Woman-Hatred

The specific targeting and extreme dehumanization of the victim suggests profound hatred of women. The “Glasgow smile” in particular is associated with disfiguring someone perceived as too attractive or too sexual.

Was Elizabeth Short Involved in Prostitution?

Contemporary media often implied or outright stated that Elizabeth was a prostitute or “party girl.” This characterization persists in some retellings of the story. However, historical evidence suggests this portrayal was largely media sensationalism.

Friends and acquaintances described Elizabeth as social and flirtatious but not promiscuous. She moved frequently, stayed with various friends and acquaintances, and struggled financially—behaviors consistent with many young women trying to make it in 1940s Hollywood, not necessarily indicative of prostitution.

The characterization of Elizabeth as promiscuous or morally questionable reflects the 1940s media’s tendency to blame female victims, suggesting they somehow deserved or invited violence through their behavior or lifestyle.

Connected Murders?

Some investigators and researchers have suggested the Black Dahlia murder might be connected to other unsolved murders in Los Angeles during the same period. Several young women were found murdered in similar circumstances between 1943 and 1949, including:

- Jeanne French (1947): Found murdered and mutilated, with writing carved into her body

- Evelyn Winters (1947): Found murdered shortly after the Black Dahlia

- Laura Trelstad (1947): Another murdered young woman found in Los Angeles

However, investigators found no definitive links between these cases, and some differences in modus operandi suggest different killers. The theory of a “Dahlia Killer” who committed multiple murders remains speculative.

Why Couldn’t Police Solve It?

Given the massive investigation, why was the Black Dahlia murder never solved? Several factors contributed:

- Contaminated crime scene: The body was discovered by civilians, and numerous people visited the scene before police arrived

- Secondary crime scene: Elizabeth was killed elsewhere, meaning the primary crime scene was never found

- Limited forensic technology: 1947 forensics were primitive compared to today—no DNA analysis, limited fingerprint databases, no security cameras

- Media interference: Newspapers compromised evidence and witnesses, sometimes paying for exclusive information

- False confessions: The volume of hoax confessions overwhelmed investigators

- Witness reluctance: Some people who might have had information were reluctant to come forward

- Possible corruption: Some researchers allege LAPD corruption may have protected certain suspects

Modern Investigations

The Black Dahlia case has never been officially closed. Periodically, new evidence or theories emerge:

- In 2003, Steve Hodel’s book renewed interest and led to re-examination of evidence

- Modern DNA technology has been applied to some physical evidence, though results have been inconclusive

- Amateur sleuths continue to investigate, sometimes discovering new witnesses or documents

- The case files, consisting of thousands of pages, continue to be studied by researchers

However, with each passing year, the likelihood of definitively solving the case diminishes. All the original suspects are long dead. Witnesses have passed away. Physical evidence has degraded or been lost over decades.

The Cultural Legacy

The Black Dahlia murder has become more than just an unsolved crime—it’s become a cultural touchstone, inspiring countless works of art, literature, and film:

- James Ellroy’s “The Black Dahlia” (1987): A noir novel that fictionalizes the case

- Brian De Palma’s film adaptation (2006): Based on Ellroy’s novel

- Countless true crime books: Dozens of books have been written about the case

- Television documentaries: Multiple TV specials and series have examined the murder

- Podcasts: True crime podcasts regularly feature the Black Dahlia case

The case has become emblematic of 1940s Los Angeles noir—a city of glamour hiding darkness underneath, where Hollywood dreams turned into nightmares.

The Real Elizabeth Short

Lost in all the speculation, theories, and media sensationalism is the real Elizabeth Short—a young woman with hopes, dreams, and a life tragically cut short.

She was born on July 29, 1924, in Hyde Park, Massachusetts. Her father abandoned the family during the Depression. She suffered from severe asthma as a child, which led her to seek California’s warmer climate for health reasons.

Friends described her as friendly, sociable, and ambitious. She worked various jobs, dreamed of becoming an actress, and like thousands of other young women, hoped to find success in Hollywood. She wrote letters home to her mother filled with optimism and dreams.

She never got the chance to achieve those dreams. At just 22 years old, she became a victim of horrific violence, and her identity became forever defined by her gruesome death rather than her life.

On January 15 each year, some people still place flowers at the site on Norton Avenue where Elizabeth Short’s body was found. The vacant lot is now developed, and the neighborhood has changed dramatically, but a small plaque marks the approximate location. Over 75 years after that terrible morning when Betty Bersinger made her horrifying discovery, the Black Dahlia case remains unsolved. The truth died with the killer, whoever he was. Was it George Hodel? Leslie Dillon? An unknown assailant who was never even investigated? We may never know. What we do know is that on a cold January night in 1947, someone committed an act of unspeakable violence against a young woman whose only crime was trying to make it in a city that promised dreams but sometimes delivered nightmares. Elizabeth Short came to Los Angeles seeking stardom and found tragedy instead. Her killer gave her infamy, but denied her justice. And so the Black Dahlia case remains what it has always been: a mystery wrapped in a nightmare, a ghost story told on the streets of Los Angeles, and a reminder that some secrets never reveal themselves, no matter how desperately we search for answers. The case files remain open. The investigation, technically, continues. But as the years pass and memories fade, the truth seems to slip further away, lost forever in the dark heart of the city that killed Elizabeth Short and then immortalized her as the Black Dahlia—a name, a legend, and a mystery that refuses to die.