On January 15, 1919, a massive tank containing over 2.3 million gallons of molasses exploded in Boston’s North End, unleashing a 25-foot wave of sticky syrup that moved at 35 miles per hour through the city streets. The deadly tsunami of molasses crushed buildings, overturned vehicles, and drowned men, women, and children in a nightmare of suffocating sweetness. Twenty-one people died. One hundred fifty were injured. The disaster sounds absurd—almost comical. But for those who lived through it, the Great Molasses Flood was pure horror, and its aftermath would change industrial safety laws forever.

The Tank on Commercial Street

In the early 20th century, Boston’s North End was a crowded immigrant neighborhood—primarily Italian and Irish families living in close quarters near the city’s industrial waterfront. The area was noisy, smelly, and densely populated, but it was home.

In 1915, the Purity Distilling Company constructed an enormous storage tank at 529 Commercial Street. The tank was a monster: 50 feet tall, 90 feet in diameter, and capable of holding 2.3 million gallons of molasses. The thick, dark syrup arrived by ship from the Caribbean and was stored in the tank before being transferred to a nearby distillery where it would be fermented into industrial alcohol—used in everything from liquor to munitions.

From the beginning, the tank was problematic. It leaked constantly. Neighborhood children would collect the dripping molasses in cans. Residents complained about the sweet, sticky residue that covered everything nearby. The tank groaned and creaked ominously, its metal plates straining under the weight of millions of gallons of viscous liquid.

But the Purity Distilling Company did nothing. They painted the tank brown to hide the leaking molasses. They ignored structural warnings. After all, it was just molasses—what harm could it do?

January 15, 1919: An Unusually Warm Day

Wednesday, January 15, 1919, dawned unseasonably warm in Boston. After days of bitter cold, the temperature suddenly climbed to around 40°F (4°C)—practically balmy for a New England January. It was lunchtime, and the North End was bustling with activity. Workers were on their breaks. Children played in the streets. Horses pulled wagons. Elevated trains rumbled overhead on Atlantic Avenue.

At approximately 12:30 PM, workers near the molasses tank heard a sound like machine-gun fire—a rapid series of metallic pops and cracks. The rivets holding the tank’s steel plates together were failing, one after another, shooting out like bullets.

Then came a roar described by witnesses as a sound like thunder or a train crash. The massive tank exploded.

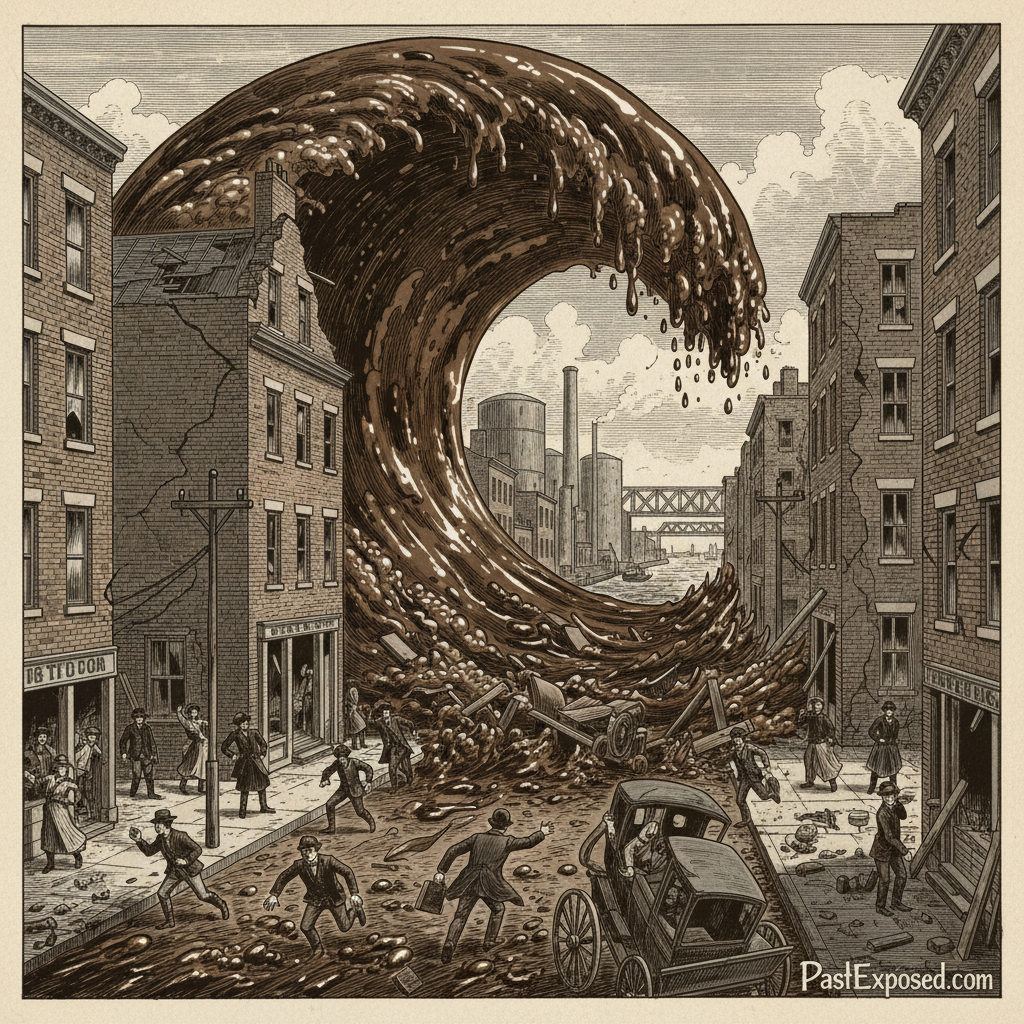

The Wave

Over 2.3 million gallons of molasses—weighing more than 13,000 tons—burst from the ruptured tank in a catastrophic flood. The initial wave was 25 feet high and moved at an estimated 35 miles per hour, a wall of dark, sticky death barreling through the crowded neighborhood.

Witnesses described the wave as moving \”like a wall of water\”—except this was far deadlier than water. Molasses is dense and viscous, 1.4 times heavier than water and incredibly difficult to escape once caught in it. The wave swept away everything in its path.

The first structure hit was the Public Works Department building. The wooden structure was demolished instantly, collapsing into splinters. Several workers inside were killed or trapped. The firehouse at Engine 31 was partially destroyed, trapping firefighters who had just moments before been enjoying lunch.

A section of the elevated railway support structure was knocked off its foundation, and a train barely stopped in time before plunging into the molasses below. Freight cars loaded with heavy goods were tossed about like toys. Horses, caught in the syrup, struggled and drowned, their screams adding to the horror.

People tried to run but couldn’t escape. The molasses was waist-deep in some areas, making movement nearly impossible. Those who fell into the flood found themselves unable to breathe as the thick syrup filled their mouths and noses. Some were pinned against buildings by the force of the wave. Others were crushed by debris carried in the flood—chunks of the tank, pieces of buildings, railroad cars.

The Victims

Twenty-one people died in the flood, their deaths horrific and suffocating:

Patrick Breen, a 44-year-old laborer, was working on a truck when the wave struck. His body was found days later, encased in hardened molasses.

William Brogan, 61, a teamster, was killed along with his horse. Both drowned in the syrup.

Bridget Clougherty, 65, was in her home when the flood demolished the building. She was pulled from the wreckage but died the next day from her injuries.

Stephen Clougherty, 34, Bridget’s son, died trying to save his mother.

John Callahan, 43, a Public Works Department employee, was crushed when the building collapsed.

Maria Distasio, 10 years old, was walking home from school. She was carried away by the wave and drowned. Her body was one of the last to be recovered, four months later, when the harbor was dredged.

The youngest victim was Pasquale Iantosca, also 10 years old. The oldest was Michael Sinnott, 78. Entire families were affected. Seven of the victims worked for the city. Several were immigrants who had come to America seeking a better life, only to die in one of the most bizarre industrial disasters in history.

The Rescue Efforts

Within minutes of the explosion, chaos reigned. The streets were covered in molasses two to three feet deep in most places, with pockets that were much deeper. The syrup flowed into cellars and basements, trapping people who had been working underground. It poured into the harbor, turning the water brown and killing fish.

Police, firefighters, and the U.S. Navy (sailors from a nearby ship, the USS Nantucket) rushed to the scene. Rescuers immediately faced an impossible challenge: how do you search for survivors in an ocean of molasses?

The syrup clung to everything. Rescuers trying to wade through it found their boots sucked off their feet. Ladders were useless because they couldn’t be placed securely. Ropes became so sticky they were nearly impossible to handle. The cold January air began to thicken the molasses, making it even harder to navigate.

Firefighters attempted to use water hoses to wash away the molasses, but water couldn’t dissolve it effectively. They needed salt water from the harbor, pumped in by fire boats, to slowly break down the syrup. It took weeks to clear the area.

Rescuers dug through collapsed buildings, pulling out victims—some alive, some dead, all covered head to toe in molasses. The smell was overwhelming: sickly sweet mixed with the stench of death. Witnesses reported that for weeks after, you could smell molasses throughout Boston. Some claimed you could still smell it in the North End on hot summer days decades later.

The Investigation

How could a tank holding molasses—a common food product—cause such destruction? The investigation revealed a perfect storm of negligence, corner-cutting, and bad engineering.

The tank had been built hastily in 1915, designed by Arthur Jell, who had no formal training in engineering. The steel plates were too thin for a structure of that size. The rivets were improperly installed, with many not fully securing the plates. No architect reviewed the design. No safety tests were conducted once the tank was built.

Company officials knew about the leaks but did nothing beyond painting the tank to hide them. They never properly tested the structure’s integrity. When the tank was filled to capacity for the first time, it leaked so badly that molasses ran down the streets. The company’s response? Send someone to collect the overflow in buckets.

The warm weather on January 15 had caused the molasses to expand. Additionally, the previous night’s cold had caused the tank’s metal to contract. When the sun warmed the tank, the metal expanded while the molasses inside, which had been cold, suddenly warmed and expanded as well. The tank, already weakened by poor construction, couldn’t handle the stress.

Carbon dioxide produced by fermentation inside the tank may have also increased internal pressure. Some historians suggest the molasses might have been fermenting slightly, producing gas that had nowhere to escape in the sealed tank.

The Legal Aftermath

The disaster triggered one of the longest and most complex legal cases in Massachusetts history. More than 100 lawsuits were filed against the United States Industrial Alcohol Company (which had bought Purity Distilling Company). The consolidated case involved 119 separate trials.

The company initially tried to blame anarchists, claiming the tank had been bombed. This was 1919, during the Red Scare, when fear of anarchist violence was high. Several bombings had occurred in Boston recently, so the theory seemed plausible. But investigators found no evidence of explosives. The cause was structural failure, pure and simple.

The legal proceedings lasted six years. In 1925, the court found United States Industrial Alcohol liable for the disaster. The company paid out approximately $628,000 in damages—roughly $11 million in today’s dollars. Victims’ families received compensation, though no amount of money could replace lost loved ones.

Changing the Law

The Great Molasses Flood had a lasting impact on engineering and construction standards. Massachusetts enacted strict new regulations requiring that all construction plans be signed and approved by a licensed architect or engineer. This became a model for building codes across the United States.

The case also established important legal precedents about corporate liability for industrial disasters. Companies could no longer claim acts of God or sabotage without evidence. They were held responsible for proper design, construction, and maintenance of dangerous structures.

The disaster highlighted the dangers of rapid industrial expansion without adequate safety oversight—a lesson that, unfortunately, has had to be relearned throughout history with each new technology and industry.

The Science of Molasses

Modern scientists have studied the Great Molasses Flood to understand the physics of the disaster. Why was it so deadly?

Viscosity: Molasses is a non-Newtonian fluid, meaning its viscosity changes with temperature and shear stress. At the temperature on January 15, the molasses was less viscous than usual, allowing it to flow quickly. But it was still dense and sticky enough to trap people and animals.

Density: Molasses is about 1.4 times denser than water, meaning a wave of molasses carries far more mass and momentum than a water wave of the same size. The force of impact was devastating.

Speed: The initial wave moved at 35 mph because of the enormous pressure release. This gave people almost no time to react or escape.

Stickiness: Once caught in molasses, escaping is nearly impossible. Unlike water, which you can swim in or wade through, molasses clings and holds. People found themselves cemented in place, unable to move their legs or lift their arms.

Urban Legend or Reality?

Over the years, some skeptics have questioned whether the disaster could have been as destructive as reported. Could molasses really kill 21 people? Could it really move at 35 mph?

The historical record is clear: the disaster was real and as terrible as described. Newspaper accounts, photographs, official investigations, and legal records all confirm the details. In 2016, a team of scientists from Harvard University even published a study in the journal *Scientific American* confirming the physics behind the flood and demonstrating that molasses could indeed flow at the reported speed and cause the documented destruction.

The Cleanup

Cleaning up after the flood took weeks. Workers used saws to cut through hardened molasses. Salt water was pumped from the harbor to dissolve the syrup. The streets were washed repeatedly, but a sticky residue remained for months.

Every surface in the North End was coated: sidewalks, buildings, fire hydrants, lampposts. People tracked molasses into their homes, into businesses, into the subway. Phone booths were sticky. The elevated train tracks were coated. For weeks, Boston was a city that stuck to itself.

Cleanup crews worked around the clock, but the molasses had infiltrated everything. It seeped into the ground, into sewers, into the foundations of buildings. Some structures had to be demolished because they were so saturated with molasses they could never be fully cleaned.

The Memory

For decades, residents of the North End claimed they could still smell molasses on hot summer days. Whether this was actual residue that had never been fully cleaned away, or a form of collective memory, is debated. But the smell became part of the neighborhood’s identity—a ghost of the disaster that nearly destroyed it.

The site of the tank is now Langone Park, a small recreational area with a Little League field. A small plaque commemorates the disaster, but most visitors have no idea what happened there. The elevated railway is gone, replaced by a different transit infrastructure. The buildings destroyed in 1919 have long since been replaced.

But the story lives on—passed down through families, studied in engineering classes, and remembered as one of the strangest and deadliest industrial disasters in American history.

The Lessons

The Great Molasses Flood reminds us that disasters can come from the most unexpected sources. A tank of syrup seems harmless—almost ridiculous as a threat. But when engineering is shoddy, when safety is ignored, when profit is prioritized over lives, even the most benign substances can become deadly.

The disaster also highlights the vulnerability of densely populated urban areas to industrial accidents. The tank was built in the middle of a residential neighborhood, surrounded by homes, schools, and businesses. Today, zoning laws would prevent such a hazardous facility from being located in a populated area. But in 1915, no such protections existed.

On a cold January day in 1919, twenty-one people left their homes for work or school, never imagining they would drown in a wave of molasses. Their deaths were preventable, caused by greed and negligence. The Great Molasses Flood stands as a testament to what happens when safety is sacrificed for profit, when warnings are ignored, and when the unthinkable becomes reality. The streets of Boston’s North End have long since been cleaned, the rubble cleared, the dead buried. But the memory remains—sticky, sweet, and horrifying. A reminder that history’s strangest disasters are often the most deadly, and that sometimes, the greatest dangers come from the places we least expect. In a world where we associate molasses with cookies and gingerbread, the Great Molasses Flood forces us to remember: anything, in sufficient quantity and with enough force, can kill. Even sweetness itself.